You are currently browsing the category archive for the ‘Folk Music’ category.

A beautiful song – with a beautiful sentiment 😉 – from Drever, McCusker, Woomble

I’m always reflective the day after Beltane (and I don’t think it’s just the hangover) so I’m posting a song by Martin Simpson which is particularly special to me…

As of tomorrow I’m booking myself in for a Digital Detox.

And to enjoy life in the slow lane I’ll be kicking back to The Unthanks…

Why not join me?

Instead of wasting you life in front of a computer screen why not learn that instrument you always wanted to play? Or kiss the next person who makes you smile? Life is short. Enjoy it.

Stay sexy.

See you soon 😉

A traditional song with significance for St Stephen’s Day/Boxing Day (26th December) beautifully performed by Chumbawamba…

Taken from the very excellent ‘English Rebel Songs 1381-1984‘.

After a rather long wait the Folk Against Fascism (FAF) website is now up and running and I’m pleased to tell you that it’s even better than expected 🙂

Apart from news and information there’s a nice selection of tunes and a blog, which is currently being written by Jon Boden of (among many, many other things) Bellowhead fame. Boden sends a very poignant message in this post where he talks about the late, great Peter Bellamy and the problem of politics in folk music…

Politics should only become an issue when political groups attempt to annexe traditional folk music/song/dance/custom to their own political agenda and attempt to restrict participation on the basis of background, politics, colour etc. This is currently the case with the BNP, and resisting that attempt is where Folk Against Fascism comes in.

Despite the leader of the British National Party (BNP), Nick Gri₤₤in, famously calling England ‘a slum’, he claims to love English folk music and has revealed that he intends to launch his own ‘folk’ radio show. But, as with all politicians, he appears to have a hidden agenda.

This weekend the BBC revealed how the BNP used one of Steve Knightly‘s songs, ‘Roots’, to raise money for their extreme right political party without his consent. When Steve discovered that one of his songs was being used on the BNP website he said…

“It’s a betrayal of your invention, you feel violated. We try to make music that’s inclusive. And when organisations like the BNP come along and say ‘this music is ours, this isn’t for black people or Jewish people or whatever’ – that’s a betrayal of what you’ve been working for.”

One of Folk Music’s brightest stars, Jon Boden, has also had found his music being taken out of context by the BNP. Along with many (many…) other projects, Jon performs with Bellowhead – the best live music act in the world!!! – and is currently one of the most influential men in British folk music, but he has found that this cannot protect his work from being misappropriated. Jon recorded several tracks for a folk album that he was told would be sold through gift shops, but he was shocked to find that it went on sale to raise money for the BNP. He says…

“The CD was titled ‘A Place Called England’, but suddenly when you see it on the BNP’s website, it takes on a darker significance that you never imagined.”

The problem is that artists have a very limited say about where and how their recorded music is used. So a new initiative is hoping to put an end to the misappropriation of British folk music. ‘Folk Against Fascism (FAF)‘ (the site should be up and running in September, but you can already join the mailing list or their Facebook group) was officially launched at Sidmouth Folk Festival last week. They hope to encourage musicians to include their logo on their CDs to make it awkward for far-right parties to sell the music or to use it for promoting their causes.

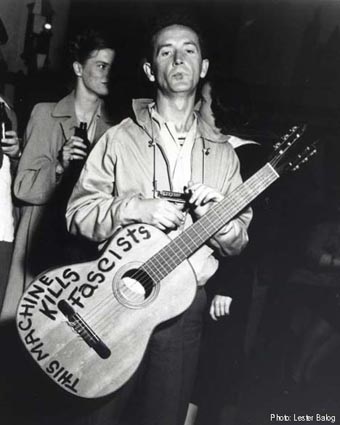

FAF’s logo is, of course, modelled on Woody Guthrie’s famous guitar…

Guthrie knew the power of music and so does FAF’s founder, Joan Crump, who says…

“Music has been a very powerful political tool, usually for the left. What concerns me is that the BNP could do the same thing from a far-right perspective.”

The BNP are said to be looking for a ‘musical soundtrack’ which will help rally people to their cause. I sincerely hope that FAF can ensure that the BNP don’t hijack folk music for these ends, but I fear that simply labelling the BNP and the far-right as ‘fascist’ may not be enough to defend the music I love. As RedStarCommando‘s blog post ‘Give Up Anti-Fascism‘ shows it hasn’t been enough to stop them with regard to elections.

FAF is an important step forward, but if it is to be truly effective it must endeavour to educate people about the real history of folk in general and British folk in particular.

Most folk music is inspired by the working class’ struggle against the oppressive forces of the wealthy and the powerful and is therefore inherently anti-fascist. Writing in The Guardian recently Marek Kohn said…

Whereas folkish nationalism sees folk music as the culture of a people, some of the most influential strands in revived and reworked folk music have seen folk songs as the culture of “the people”, a group defined in opposition to their lords and masters, rather than to counterparts in other lands. The idea of connecting with the people still strikes chords – and folk’s substantial communist heritage still seems to be regarded as perfectly unproblematic.

But like so many on the left he underplays the importance of a shared cultural history. Interestingly enough he also quoted Steve Knightley who urges the English to “rediscover … their musical identity” because “we need roots”, but responds…

Do we really, though? We need depth and we need substance, but we are not plants. At different times different peoples may need the strength that their roots give them, but at this point in history the English scarcely lack sources of support or enrichment. We enjoy affluence and access to knowledge far beyond the imaginations of those unknowns who created the ballads of the British folk canon.

Apart from ignoring the facts that Britain remains one of the most class divided societies on the planet and that high levels of affluence have brought equally high levels of anxiety, depression and suicide thanks largely to the alienating nature of our rootless consumer existence; this statement reflects a widely held feeling on the left that the cultural history of a country should be abandoned for fear that any positive statement could be confused with ardent nationalism.

But anyone who bothers to look at the real, everyday history of the English working class will find a tradition to be – dare I say it… – proud of.

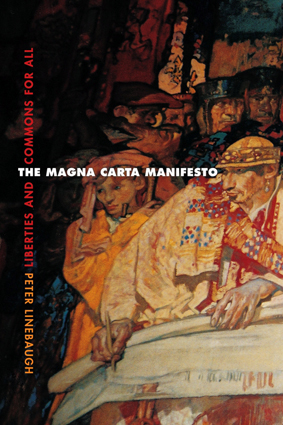

History, as Alex Haley famously said, “is written by the winners” and English history is usually presented as a list of Kings and Queens which begins in 1066 and peaks with the Victorian imperialism of the British Empire. But this is the history of a privileged and the powerful elite. The real history and culture of England is enshrined by tales (both factual and mythical – i.e. folklore) of everyday people who have stood up to excesses and abuses of power in favour of the Liberties of England as enshrined by Magna Carta (which, as Peter Linebaugh demonstrates in his groundbreaking The Magna Carta Manifesto: Liberty & Commons for All, remain of global importance).

England is the home of Robin Hood and ‘Freeborn’ John Lilburne; Ned Ludd and Wat Tyler; Captain Swing and Bartholomew Steer. An overwhelming number of our popular histories, myths and legends contain within them the core English values of liberty, solidarity, collectivism, mutuality, political radicalism, social justice and self-determinism. We would do ourselves an immense disservice if we were to disregard such a rich cultural heritage in the name of ideology or, worse still, political correctness.

Instead folklorists, historians and musicians should endeavour to present a more balanced view of English history, culture and tradition; one that celebrates the English working class and the Liberties of England. As I attempted to show with regard to the issue of ‘blacking‘ in Border Morris, a deeper understanding of our traditions is the best weapon against fear, hatred and ignorance.

Music may indeed be a powerful tool; but so is knowledge.

Further reading

George Orwell ‘Essays‘

The essays of George Orwell may have been written over 60 years ago, but they remain relevant to the ‘English experience’ and manage to balance a love of England with a hatred of ardent nationalism. Of particular interest to this article would be The Lion & The Unicorn, My Country Left or Right and Notes On Nationalism.

E. P. Thompson ‘The Making of the English Working Class‘

The book that revolutionised our understanding of English social history.

Paul Kingsnorth ‘Real England‘

Paul Kingsnorth searches for an English cultural and political identity which is based on ‘being’ rather than ‘belonging’, or, as Paul says, “a new type of patriotism, benign and positive, based on place not race, geography not biology.”

The blog for Paul’s book can be found here

The law locks up the man or woman

Who steals the goose from off the common

But lets the greater villain loose

Who steals the common from the goose- AnonymousIn every cry of every Man,

In every Infants cry of fear,

In every voice: in every ban,

The mind-forg’d manacles I hear.- William Blake

Earlier this year the Motley Morris troupe from Dartford, Kent were booked to dance at a primary school, but when the school found out that their routine involved ‘blacking’ – the use of burnt cork to paint the dancers faces – they were asked not to attend due to fears they could cause offence.

A spokesman for Motley Morris, Simon Fordis was quoted in The Independent as saying…

“Our style of morris dancing originates from the Welsh/Shropshire borders. Our blackened faces are a form of disguise. Traditionally they used burnt cork, which came out black, but if it had come out red then we would have had red faces, that’s all it is. It’s part of our English culture which goes back hundreds of years, it’s an age-old tradition. [sic]They said it was supposed to be a cultural evening but they hadn’t even bothered to find out why it is we have blackened faces. They’re obviously afraid of upsetting someone.”

The headteacher of the school stated…

“We found ourselves in a difficult position of weighing up any potential offence versus not wishing to compromise the morris dancers’ tradition. It’s a ‘damned if we do, damned if we don’t’ scenario and quite understandably it will be a talking point as to the rights and wrongs of our decision. I apologise to the morris troupe for any inconvenience caused and ask for people’s understanding at what was a difficult but well intended decision.”

This is indeed a ‘damned if we do, damned if we don’t’ issue, but it is one that has been confounded by an ignorance of working-class history and by our currently shallow, point-scoring, right-vs-left, political culture. Obviously far-right bloggers made a big deal of this event with the usual “What about the indigenous (meaning ‘white’) English and their traditions” line (the far right like to talk about ‘history’ and ‘tradition’, but show little knowledge of either), whereas the right wing in general replied with the incredibly hackneyed “Political Correctness gone mad”. But the ‘right-on’ left were equally as predictable with their “morris is a Victorian invention” and “imperialist traditions” type comments.

Which is a shame because if they had bothered to look deeper they would have found that blacking was once an aspect of an everyday, grassroots movement which fought for social, economic and racial equality.

You may be wondering why morris dancers need a ‘disguise’; are they really that embarassed by their hobby? Obviously there’s more to this tradition than some fancy footwork.

A chapter of Peter Linebaugh’s incredibly important book, “The Magna Carta Manifesto: Liberty & Commons For All” (UC Press, 2008), entitled ‘Charters of Liberty in Black Face and White Face: Race Slavery & The Commons’ deals specifically with the themes of blacking and race. I recommend that you buy this book or ask your local library to stock it; luckily if you are unable – or unwilling – to get your hands on a copy, the cool guys at Mute magazine have an online version of the chapter in question; this chapter on it’s own acts as a great introduction to the ideas presented in Linebaugh’s book.

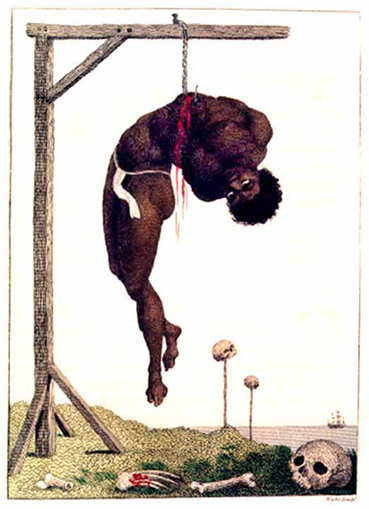

Linebaugh reveals that blacking was used as a disguise by people who were fighting for their traditional Liberties as guaranteed under Magna Carta. He describes the fateful events which led to the notorious Waltham Black Act of 1722 and shows that it wasn’t just ‘poaching’ which led to the passing of this law. After coming across the anonymously published The History of the Blacks of Waltham in Hampshire (1723) Linebaugh became convinced that he needed to…

put forward the fact that the poachers defended commoning, not just by disguising themselves but by disguising themselves as Negroes, and they did so at Farnham, near the heart of what became the quintessence of England as Jane Austen so gently wrote about it, or Gilbert White, the ornithologist, so carefully observed it, or William Cobbett, the radical journalist, so persistently fulminated about it.

He goes on to describe the events at Farnham, a town north of Portsmouth and just 60 miles Southeast of Motley Morris’s hometown of Dartford and shows how this the stage for a legal definition of ‘race’…

Round about Farnham timber was wanted for the construction of men-of-war and East Indiamen which stopped in Portsmouth for repairs, or were built there from scratch for the purpose of the globalisation of commodity trade characteristic of the time. Here’s how a flashpoint in the episodes of the Waltham Blacks began: ‘Mr. Wingfield who has a fine Parcel of growing Timber on his Estate near Farnham fell’d Part of it: The poor People were admitted (as is customary) to pick up the small Wood; but some abusing the Liberty given, carry’d off what was not allow’d, which that Gentleman resented; and, as an Example to others, made several pay for it. Upon which, the Blacks summon’d the Myrmidons, stripp’d the Bark off several of the standing Trees, and notch’d the Bodies of others, thereby to prevent their Growth; and left a Note on one of the maim’d Trees, to inform the Gentleman, that this was their first Visit; and that if he did not return the Money receiv’d for Damage, he must expect a second from … the Blacks.’ This is not exactly tree-hugging or Indian chipko, though it did have warrant among local antiquarians in the nineteenth century who searched for a charter of such commoning. The leader of the Blacks and ‘15 of his Sooty Tribe appear’d, some in Coats made of Deer-Skins, others with Fur Caps, &c. all well armed and mounted: There were likewise at least 300 People assembled to see the Black Chief and his Sham Negroes….’

Charles Withers, Surveyor-General of Woods, observed in 1729 ‘that the country people everywhere think they have a sort of right to the wood & timber in the forests, and whether the notion may have been delivered down to them by tradition, from the times these forests were declared to be such by the Crown, when there were great struggles and contests about them, he is not able to determine.’ The Waltham Blacks, they said, ‘had no other design but to do justice, and to see that the Rich did not insult or oppress the poor.’ They were assured that the chase was ‘originally design’d to feed Cattle, and not to fatten deer for the clergy, &c.’ The central common right was pasture, ‘common of herbage’ as the Forest Charter says. Keeping a cow was possible on two acres, and less in a forest or fen. Half the villagers of England were entitled to common grazing. As late as the 18th century ‘all or most householders in forest, fen, and some heathland parishes enjoyed the right to pasture cows or sheep.’ So, the Waltham Blacks were class conscious. There was also an awareness at the time that the keeping of a cow, essential to the material constitution of the country, was backed up by charter.

Timothy Nourse denounced commoners at the beginning of the century. They were ‘rough and savage in their Dispositions.’ They held ‘leveling Principles.’ They were ‘insolent and tumultuous’ and ‘refractory to Government.’ In September 1723 Richard Norton, the Warden of the Forest of Bere, wished to ‘put an end to these arabs and banditti.’ The commoner belonged to a ‘sordid race.’

The commoner was compared to the Indian, to the savage, to the buccaneer, and to the Arab.(emphasis added)

The ‘Blacks’ defended the customs of the commoners; the commoners were both criminalised and racialised in the discourse of the enclosers, the privatisers, and the big wigs. There was even the suggestion that attacking them was a sort of crusade. The Waltham Black Act of 1722 thus became, among other things, a means of drawing a colour line and criminalising common right.

This drawing of the ‘colour line’ – and indeed the Waltham Black Act – was to prove essential to the development of one of the largest and most hideous trades in history – the slave trade.

William Blake

Naturally the slave trade went against ‘Christian values’ and the belief that ‘all men are equal before God’, but it was big business and – as well we know from that day to this – money-men will stop at nothing to make a profit. As ever divide and conquer was the preferred strategy…

A buffer stratum was to be created by offering material advantages to white proletarians to the lasting detriment of black proletarians. When and how did the ‘wages of whiteness’ originate? The first date DuBois gives in the protracted process is 1723 when laws were passed in Virginia making Africans and Anglo-Africans slaves forever. The bonded people objected in 1723 to the Bishop of London and the King ‘and the rest of the Rullers.’ ‘Releese us out of this Cruell Bondegg’ they cried. In the same year Richard West, the Attorney General, objected to the same law, ‘I cannot see why one freeman should be used worse than another, merely upon account of his complexion….’ But the Governor of Virginia understood the necessity of ‘a perpetual Brand’ – skin colour, or the phenotype, which marked the person as surely as the burnt flesh caused by the golden brands used by the South Sea Company. In this way, Ted Allen tells us, a ‘monstrous social mutation’ occurred, namely, that stratum within the American class structure which derives its hopes, security, and welfare from white skin privilege. It has been essential to the constitution of American class relations ever since.

Slavery was abolished in England in 1807, The Black Act was abolished in 1823 and the Slavery Abolition Act was introduced in 1833, but the colour line that the Black Act and the Slave Trade helped to create remains politically and socially divisive to this day.

Ignorance lies at the heart of bigotry; unfortunately the politically correct left seem to be willfully ignorant of English working-class traditions, even though these traditions can reveal a cultural history that could bring modern English citizens – of all races – closer together.

“We found ourselves in a difficult position of weighing up any potential offence versus not wishing to compromise the morris dancers’ tradition.

“It’s a ‘damned if we do, damned if we don’t’ scenario and quite understandably it will be a talking point as to the rights and wrongs of our decision.

“I apologise to the morris troupe for any inconvenience caused and ask for people’s understanding at what was a difficult but well intended decision.”

One of my favourite places anywhere on this beautiful Isle of Albion is the stretch of Yorkshire coastline at Bempton Cliffs, between Bridlington and Scarborough. One of the best ways to enjoy this landscape is by walking the cliff-tops along the Headland Walk. This walk is usually pretty accessible – though I did run into a couple of problems this year – unfortunately this is not the story for much of England’s coast . Admittedly coastal erosion and unseasonably wet summers – which are great for rapid plant growth – have not helped, but coastal walkers in England routinely have to face barbed wire, farm machinery, cattle, unkempt paths and even live ammunition. Thankfully all this is about to change…

New maps have been released that detail 2,748 miles of coastal paths that Natural England is preparing to open up to shoreline walkers.

Picture from The Guardian

The Guardian reports…

Maps drawn up for the marine and coastal access bill, which is expected to become law in November, trace a vivid red and green snake round the 2,748 miles of mainland coast. Each of the red sections is either private, inaccessible or dangerous.

The audit by Natural England and shoreline councils is part of an effort to make all of England’s coastline accessible to walkers. “There will be 10 years’ work to be done before we can walk the whole way,” said Paul Johnson, coastal access manager for Natural England, “but we reckon that the first rights of way between major seaside towns could be in place by 2013.”

Which is great news for walkers 🙂

Apart from the landscape and bird-life Scarborough is also close to my heart because of the beautiful ballad, Scarborough Fair. This song appears to derive from an older (and now obscure) Scottish ballad called ‘The Elfin Knight‘; a version of which appears on Kate Rusby’s 2005 album, ‘The Girl Who Couldn’t Fly’.

Scarborough Fair was itself made famous by Simon & Garfunkel…