You are currently browsing the tag archive for the ‘morris dancing’ tag.

The law locks up the man or woman

Who steals the goose from off the common

But lets the greater villain loose

Who steals the common from the goose- AnonymousIn every cry of every Man,

In every Infants cry of fear,

In every voice: in every ban,

The mind-forg’d manacles I hear.- William Blake

Earlier this year the Motley Morris troupe from Dartford, Kent were booked to dance at a primary school, but when the school found out that their routine involved ‘blacking’ – the use of burnt cork to paint the dancers faces – they were asked not to attend due to fears they could cause offence.

A spokesman for Motley Morris, Simon Fordis was quoted in The Independent as saying…

“Our style of morris dancing originates from the Welsh/Shropshire borders. Our blackened faces are a form of disguise. Traditionally they used burnt cork, which came out black, but if it had come out red then we would have had red faces, that’s all it is. It’s part of our English culture which goes back hundreds of years, it’s an age-old tradition. [sic]They said it was supposed to be a cultural evening but they hadn’t even bothered to find out why it is we have blackened faces. They’re obviously afraid of upsetting someone.”

The headteacher of the school stated…

“We found ourselves in a difficult position of weighing up any potential offence versus not wishing to compromise the morris dancers’ tradition. It’s a ‘damned if we do, damned if we don’t’ scenario and quite understandably it will be a talking point as to the rights and wrongs of our decision. I apologise to the morris troupe for any inconvenience caused and ask for people’s understanding at what was a difficult but well intended decision.”

This is indeed a ‘damned if we do, damned if we don’t’ issue, but it is one that has been confounded by an ignorance of working-class history and by our currently shallow, point-scoring, right-vs-left, political culture. Obviously far-right bloggers made a big deal of this event with the usual “What about the indigenous (meaning ‘white’) English and their traditions” line (the far right like to talk about ‘history’ and ‘tradition’, but show little knowledge of either), whereas the right wing in general replied with the incredibly hackneyed “Political Correctness gone mad”. But the ‘right-on’ left were equally as predictable with their “morris is a Victorian invention” and “imperialist traditions” type comments.

Which is a shame because if they had bothered to look deeper they would have found that blacking was once an aspect of an everyday, grassroots movement which fought for social, economic and racial equality.

You may be wondering why morris dancers need a ‘disguise’; are they really that embarassed by their hobby? Obviously there’s more to this tradition than some fancy footwork.

A chapter of Peter Linebaugh’s incredibly important book, “The Magna Carta Manifesto: Liberty & Commons For All” (UC Press, 2008), entitled ‘Charters of Liberty in Black Face and White Face: Race Slavery & The Commons’ deals specifically with the themes of blacking and race. I recommend that you buy this book or ask your local library to stock it; luckily if you are unable – or unwilling – to get your hands on a copy, the cool guys at Mute magazine have an online version of the chapter in question; this chapter on it’s own acts as a great introduction to the ideas presented in Linebaugh’s book.

Linebaugh reveals that blacking was used as a disguise by people who were fighting for their traditional Liberties as guaranteed under Magna Carta. He describes the fateful events which led to the notorious Waltham Black Act of 1722 and shows that it wasn’t just ‘poaching’ which led to the passing of this law. After coming across the anonymously published The History of the Blacks of Waltham in Hampshire (1723) Linebaugh became convinced that he needed to…

put forward the fact that the poachers defended commoning, not just by disguising themselves but by disguising themselves as Negroes, and they did so at Farnham, near the heart of what became the quintessence of England as Jane Austen so gently wrote about it, or Gilbert White, the ornithologist, so carefully observed it, or William Cobbett, the radical journalist, so persistently fulminated about it.

He goes on to describe the events at Farnham, a town north of Portsmouth and just 60 miles Southeast of Motley Morris’s hometown of Dartford and shows how this the stage for a legal definition of ‘race’…

Round about Farnham timber was wanted for the construction of men-of-war and East Indiamen which stopped in Portsmouth for repairs, or were built there from scratch for the purpose of the globalisation of commodity trade characteristic of the time. Here’s how a flashpoint in the episodes of the Waltham Blacks began: ‘Mr. Wingfield who has a fine Parcel of growing Timber on his Estate near Farnham fell’d Part of it: The poor People were admitted (as is customary) to pick up the small Wood; but some abusing the Liberty given, carry’d off what was not allow’d, which that Gentleman resented; and, as an Example to others, made several pay for it. Upon which, the Blacks summon’d the Myrmidons, stripp’d the Bark off several of the standing Trees, and notch’d the Bodies of others, thereby to prevent their Growth; and left a Note on one of the maim’d Trees, to inform the Gentleman, that this was their first Visit; and that if he did not return the Money receiv’d for Damage, he must expect a second from … the Blacks.’ This is not exactly tree-hugging or Indian chipko, though it did have warrant among local antiquarians in the nineteenth century who searched for a charter of such commoning. The leader of the Blacks and ‘15 of his Sooty Tribe appear’d, some in Coats made of Deer-Skins, others with Fur Caps, &c. all well armed and mounted: There were likewise at least 300 People assembled to see the Black Chief and his Sham Negroes….’

Charles Withers, Surveyor-General of Woods, observed in 1729 ‘that the country people everywhere think they have a sort of right to the wood & timber in the forests, and whether the notion may have been delivered down to them by tradition, from the times these forests were declared to be such by the Crown, when there were great struggles and contests about them, he is not able to determine.’ The Waltham Blacks, they said, ‘had no other design but to do justice, and to see that the Rich did not insult or oppress the poor.’ They were assured that the chase was ‘originally design’d to feed Cattle, and not to fatten deer for the clergy, &c.’ The central common right was pasture, ‘common of herbage’ as the Forest Charter says. Keeping a cow was possible on two acres, and less in a forest or fen. Half the villagers of England were entitled to common grazing. As late as the 18th century ‘all or most householders in forest, fen, and some heathland parishes enjoyed the right to pasture cows or sheep.’ So, the Waltham Blacks were class conscious. There was also an awareness at the time that the keeping of a cow, essential to the material constitution of the country, was backed up by charter.

Timothy Nourse denounced commoners at the beginning of the century. They were ‘rough and savage in their Dispositions.’ They held ‘leveling Principles.’ They were ‘insolent and tumultuous’ and ‘refractory to Government.’ In September 1723 Richard Norton, the Warden of the Forest of Bere, wished to ‘put an end to these arabs and banditti.’ The commoner belonged to a ‘sordid race.’

The commoner was compared to the Indian, to the savage, to the buccaneer, and to the Arab.(emphasis added)

The ‘Blacks’ defended the customs of the commoners; the commoners were both criminalised and racialised in the discourse of the enclosers, the privatisers, and the big wigs. There was even the suggestion that attacking them was a sort of crusade. The Waltham Black Act of 1722 thus became, among other things, a means of drawing a colour line and criminalising common right.

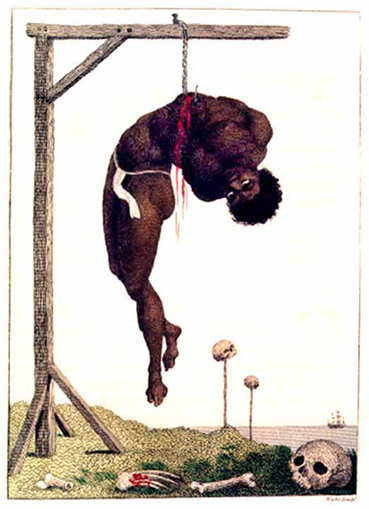

This drawing of the ‘colour line’ – and indeed the Waltham Black Act – was to prove essential to the development of one of the largest and most hideous trades in history – the slave trade.

William Blake

Naturally the slave trade went against ‘Christian values’ and the belief that ‘all men are equal before God’, but it was big business and – as well we know from that day to this – money-men will stop at nothing to make a profit. As ever divide and conquer was the preferred strategy…

A buffer stratum was to be created by offering material advantages to white proletarians to the lasting detriment of black proletarians. When and how did the ‘wages of whiteness’ originate? The first date DuBois gives in the protracted process is 1723 when laws were passed in Virginia making Africans and Anglo-Africans slaves forever. The bonded people objected in 1723 to the Bishop of London and the King ‘and the rest of the Rullers.’ ‘Releese us out of this Cruell Bondegg’ they cried. In the same year Richard West, the Attorney General, objected to the same law, ‘I cannot see why one freeman should be used worse than another, merely upon account of his complexion….’ But the Governor of Virginia understood the necessity of ‘a perpetual Brand’ – skin colour, or the phenotype, which marked the person as surely as the burnt flesh caused by the golden brands used by the South Sea Company. In this way, Ted Allen tells us, a ‘monstrous social mutation’ occurred, namely, that stratum within the American class structure which derives its hopes, security, and welfare from white skin privilege. It has been essential to the constitution of American class relations ever since.

Slavery was abolished in England in 1807, The Black Act was abolished in 1823 and the Slavery Abolition Act was introduced in 1833, but the colour line that the Black Act and the Slave Trade helped to create remains politically and socially divisive to this day.

Ignorance lies at the heart of bigotry; unfortunately the politically correct left seem to be willfully ignorant of English working-class traditions, even though these traditions can reveal a cultural history that could bring modern English citizens – of all races – closer together.

“We found ourselves in a difficult position of weighing up any potential offence versus not wishing to compromise the morris dancers’ tradition.

“It’s a ‘damned if we do, damned if we don’t’ scenario and quite understandably it will be a talking point as to the rights and wrongs of our decision.

“I apologise to the morris troupe for any inconvenience caused and ask for people’s understanding at what was a difficult but well intended decision.”