You are currently browsing the tag archive for the ‘england’ tag.

This Saturday there will be a protest against the BNP in Morley, Yorkshire. This is an important event, as Folk Against Fascism say…

Nick Griffin believes Morley & Outwood is the BNP’s top target in Yorkshire. And for good reason. BNP member Chris Beverley is already a councillor in the area — and in the 2008 local elections, the BNP polled more votes than any other party.

Morley & Outwood Day of Action

Saturday, 17 April, 2010,10:30 AM – 3:30 PM

Unity Hall, 2 Commercial Street, Morley, LS27 8HY

For various reasons (largely work related 😦 ) this blog has been pretty quiet recently. But after re-reading Paul Kingsnorth’s ‘What England Means to Me’ post I have been reminded of the reasons why I created this blog in the first place. I cannot be the only person to LOVE ENGLAND, HATE FASCISM, so from now on I shall endeavour to try harder – i.e. post more blogs and actively fight for the English Libertarian cause. In the meantime here’s Paul’s excellent post…

What England Means to Me

Paul Kingsnorth

A few years back, I found myself in a narrow valley on the border between England and Wales. There are some landscapes – fewer as time passes – in which it seems that time has, if not exactly stood still, then been hijacked by some outside force for its own ends. There are some landscapes in which you can sense the ancient heart of the place in the air. This was one of them.

It was a landscape of scattered hill farms, high moors, hedge-lined holloways and winding brooks. Save for the odd industrial shed tacked on to a farmyard, or barbed wire fence, there was little of contemporary England about it. There were few cars. And everywhere, there were textures.

The textures of this valley became more and more noticeable as I walked its length. I took out my camera and began to photograph them at close quarters. Robbed of their wider context they look, when printed, like abstractions. The jigsaw bark of an old tree; white air bubbles on the surface of a blue pond; another tree’s bark, glossy this time and mottled; green moss on a purple gravestone; tree roots snaking through the dust; the parallel lines of a corrugated iron roof.

A legion of textures, colours, surfaces, pictures, crowding in on one another; the patchy, unplanned, diversity of place. This is what England means to me. Place, above all, is what makes my England. A small nation, shaped by humans for millennia, has no place which does not bear the mark of that shaping. Contemporary England is a patina; a palimpsest of historical eras, of times, of peoples. Everywhere there is colour, culture, history.

But England means something else, too. England means the rise of capital; the birthplace of the industrial revolution. England means enclosure, and empire. England invented much of the modern world, and what it invented is now destroying it. England is eating itself.

Look around you. Where are those textures? What is happening to them? Where I live, the texture of place is rapidly being overrun by the corporate non-places which our economic progress apparently requires of us: the malls, the motorways, the clone stores; the faceless ragbag of globalised, plasticised corporate clutter which allows us to “grow” and “compete” and remain players in a global economy which is spiralling out of control. It is an economy which eats up colour and character and spits our conglomeration and control. In the Brave New World of flexible labour markets, 24-hour consumerism and £5 air tickets, belonging to a place and having any feeling for it is a serious stumbling block on the road to the future.

But what England also means to me is the spirit of its people: a spirit which has at its heart a contradiction. One the one hand the English are – frustratingly – some of the most obedient people on Earth. Their pubs can be sold off for executive flats, their landscapes ripped apart by motorways, their folk culture scorned, their community gathering points shut down in the name of Health and Safety, their high streets scoured out by Tesco – and most of them will just shrug their shoulders, moan about the government and head for the out-of-town shopping centre. Sometimes, the English could do with being a bit more – well, French.

And yet there is another English spirit too, which arouses in me hope rather than despair. It is the spirit which marches to save Post Offices; which ties itself to bulldozers to save beauty spots from destruction; which saves its local pub and fights yet another shopping mall development in its historic towns. It is, perhaps, the spirit channelled by Gerrard Winstanley, John Ball, John Clare, William Morris – and William Cobbett, who railed two hundreds years ago against “The Thing”. The Thing is still with us. It’s bigger now, and greedier and it eats texture, patina, place and peculiarity for breakfast. But maybe – just maybe – England is beginning to wake up. I hope so.

Paul Kingsnorth’s book Real England is published by Portobello. www.realengland.co.uk

If I had as many lives as I have hairs on my head

or drops of blood in my veins,

I would give them all up for this cause,for the Liberties of England!

John Bastwick (as quoted on Rev Hammer's 'Freeborn John' album)

These are troubled times both for Liberty and for Democracy; each of these concepts is, of course, meaningless without the other. Liberties that took 500 years and countless lives to secure are being rolled back in the name of ‘security’ by a self-serving political elite who treat the democratic process and the electorate with undisguised contempt. To cite security as a reason to deny liberty shows that the politicians – on both sides of the Atlantic – have learnt nothing in the 250 years since Benjamin Franklin famously wrote…

“They who would give up essential liberty to purchase a little temporary safety, deserve neither liberty nor safety.”

from the title page of An Historical Review of the Constitution and Government of Pennsylvania. 1759

In truth it is not just the years that divide today’s politicians from their enlightenment forebears. There was once a commitment – in philosophy at least, if not in practice – to the belief that government should be no more than a tool that exists to guarantee and protect the basic freedoms and liberties of it’s people so that each person might live as full a life as possible. This sentiment was best summed up in the motto “That government is best which governs least” (often attributed to Thomas Jefferson or Thomas Paine, but actually made famous by Henry David Thoreau’s 1849 essay, ‘Civil Disobedience‘ wher he paraphrases the motto of The United States Magazine and Democratic Review: “The best government is that which governs least.”).

But modern governments are all too willing to try and control every aspect of human life and few of us today feel that government and politicians are acting in the interests of the people.

The Liberties of England should be our proudest achievement; the social, economic and legal rights enshrined by Magna Carta (both the Great Charter and The Charter of the Forest – see Peter Linebaugh’s ‘The Magna Carta Manifeston: Liberties and Commons for all.‘) have had a global influence beyond the imagination of the Barons who drafted them – and I believe that they will continue to be of immense symbolic importance as we enter the third millennium. These documents were cited during the English, French and American revolutions and were even mentioned during the 1994 Zapatista uprising, but in today’s Britain the basic liberties of habeas corpus, trial by jury, the right to silence, due process and the right to free speech are all being threatened by the government’s supposed attempts at fighting ‘terrorism’ and ‘organised crime’.

The legal system of England and Wales has never been perfect and is far from impartial, but rather than attempt to democratise the judiciary the Labour government has chosen to bypass it altogether. A fundamental principle of justice is that the same person or authority that brings a criminal allegation against an individual should not then decide whether that person is guilty – i.e. the police make an arrest and then the courts decide upon guilt. This is essential if we believe that a person is innocent before being proved guilty. But the government’s Anti-Social Behaviour Order (ASBO) and subsequent related laws have effectively made the police- and, worse still, local authorities – judge, jury and executioner regarding a large number of offences. And despite the Labour government creating over 3000 new criminal offences since 1997 violent crime (all crimes against the person have to be considered the worst possible crimes in a humane society) has risen by nearly 80%.

![Knife Crime[6] Knife Crime[6]](https://wynfrith.wordpress.com/wp-content/uploads/2009/08/knife-crime6.jpg?w=490)

Lady Justice - now dumb as well as blind!

In relation to ‘crime’ and the ‘terrorist threat’ we are also witnessing a widespread and ongoing abuse of the basic right to privacy. The famous 16th Century barrister, Sir Edward Coke helped to revive a general interest in Magna Carta and his work would heavily influence both English and American revolutionaries. Coke’s best known statement is arguably…

“For a man’s house is his castle, et domus sua cuique est tutissimum refugium [and each man’s home is his safest refuge].”

…from whence we get the quote “An Englishman’s home is his castle”. But today our ‘castles’ are being stormed (or at least placed under seige…) ‘for our own protection’ and privacy has become yet another victim of security.

The sad truth, of course, is that the more we are denied our hard-fought liberties the weaker our democracy becomes; which, in turn, undermines the government’s claims that the ‘war on terrorism’ is a battle for democracy and freedom. Marcus Aurelius said “The best revenge is to be unlike him who performed the injury.“; if we give up an ounce of liberty then we ourselves become an enemy of democracy. Not that we English have much democracy left to lose…

In Britain government (both national and European) is becoming ever more invasive and is slowly creeping into every corner of our lives whilst giving us fewer and fewer opportunities to influence, oppose or even debate important political decisions. In England the situation is even more bleak; since devolution we are the only county in the EU which does not have it’s own parliament or national assembly. For better or worse decisions that directly effect the citizens of England are not solely in the hands of English citizens. The following quote cited by The Witanagemot Club shows the worrying extent of this problem…

Encyclopedia Britannica : England

Outside the British Isles, England is often erroneously considered synonymous with the island of Great Britain ( England , Scotland , and Wales ) and even with the entire United Kingdom . Despite the political, economic, and cultural legacy that has secured the perpetuation of its name, England no longer officially exists as a governmental or political unit—unlike Scotland, Wales, and Northern Ireland, which all have varying degrees of self-government in domestic affairs. It is rare for institutions to operate for England alone. Notable exceptions are the Church of England ( Wales , Scotland , and Ireland , including Northern Ireland , have separate branches of the Anglican Communion) and sports associations for cricket, rugby, and football (soccer). In many ways England has seemingly been absorbed within the larger mass of Great Britain since the Act of Union of 1707.’ — Encyclopedia Britannica, 2004.

This is known as “the West Lothian Question” after a 1977 speech by Tam Dalyell, the then Scottish Labour MP for West Lothian, in which he stated…

For how long will English constituencies and English Honourable members tolerate… Honourable Members from Scotland, Wales and Northern Ireland exercising an important, and probably often decisive, effect on English politics while they themselves have no say in the same matters in Scotland, Wales and Northern Ireland?

This situation is further exacerbated by the fact that local governments – which should be on the front line of democracy – have been robbed of any real power. In all but the smallest councils the committee system – which helped local residents have at least some say in local government – has been replaced by dictates from central government, ‘elected mayors’ (or ‘strong leaders’), quangos and/or almos – all with the minimum of accountability. In 2006 a report by the Joseph Rowntree Foundation’s POWER Inquiry concluded that the deep rooted problems with British democracy are “systemic not personal”; in general neither the public nor the politicians are guilty of apathy(though it is the politicians who have the most to gain from the current state of affairs), but the present system creates a high level of political alienation combined with extremely low levels of confidence which, in turn, leaves both the public and the politicians feeling powerless. English Democracy – which has existed on and off in one form or another since the 7th Century – may not be dead, but it’s in a critical condition.

Unfortunately no single political party or independent politician is in a position to single-handedly change this worrying state of affairs even if they wanted to. What’s needed is the most far reaching constitutional change to be seen in England since the Civil Wars or the Act of Union! (I am stressing the English problem as the population of England are in a rather unique political situation; citizens of Wales and Northern Ireland are only marginally better off – remember we’re talking solely about democratic rights here – and the citizens of Scotland are in the best position, relatively speaking. But Britain as a whole remains in crisis with regard to liberty and democracy – so Britain as a whole must work towards a solution).

Luckily we are beginning to see the first signs of a much needed people’s movement for change. The aforementioned Joseph Rowntree Trust have just taken over the Real Change campaign which was launched (originally as ‘Magna Carta 2.0’, which I personally thought was a better title) by members of openDemocracy to try and encourage…

- An intelligent self-governing citizens’ movement for much better democracy and liberty in Britain

- A serious debate about the future of modern democracy, liberty and human rights, drawing on the best of international ideas.

The Real Change site says…

We aim to bring this movement into being through a new group: Real Change: the open politics network. The parties and politicians cannot be relied upon to deliver real change for us [sic]. Citizens have to be in the driving seat. Recent pronouncements by the Prime Minister and the leader of the opposition offer little more than vague and cosmetic changes. “Reform so as to preserve” is still the mantra of the political elite, who hope the wave of popular outrage will once again crash and dissipate into passive acquiescence.

Blogland is awash with people of all political persuasions drawing much the same conclusions. Old differences are being set aside as people realise that ideology will count for nothing if we do not address the current crisis of democracy, liberty and human rights. But this fight will not be won in cyberspace; if we are to protect the Liberties of England we must endeavour to bring the campaign to the people.

What I am about to suggest is not a campaign in it’s own right, it is simply a strategy to get people talking. We need a highly visible, non-partisan, popular symbol to signify a heartfelt commitment to regain, preserve and expand our aforementioned democracy, liberty and human rights. (We also need non-partisan democracy, but that’s another story – or rather another blog post.)

I want to re-introduce the sea-green ribbon as a symbol of liberty and democracy.

Sea-green ribbons were worn by members and supporters of the Levellers during the English Revolution. The movement began in July 1646 when people came together to petition parliament in an attempt to free John Lilburne, England’s greatest unsung hero, from the Tower of London where he faced the death penalty on grounds of ‘treason’ (Lilburne remains the only man to be tried for treason by both the crown and by parliament). Known as ‘Freeborn John’, Lilburne is admired across the political spectrum because his life physically embodied a sense of freedom that remains an inspiration for us all.

The Levellers were a short lived movement (thanks mainly to the duplicity and cruelty of Cromwell), but their legacy remains relevant even today. As we can see from their main documents (see Richard Overton’s ‘An Arrow Against All Tyrants‘, ‘The Agreement of the People‘ and ‘An Agreement of the Free People‘) and transcripts of The Putney Debates the Levellers believed in the Liberties of England, equality and social justice. Among other things, Tony Benn (speaking at the annual Levellers Day event in Burford, Oxfordshire) has cited a few central beliefs that he believes would be of significance today (please do not take this as a nod to ‘the left’, I have already stated that the crisis of liberty is such that it is more important than political allegiance – to which I am ‘left-libertarian’)…

The Levellers would uphold the rights of the people to recall and replace their parliamentary candidates because of the inalienable sovereignty of the people which no Parliament has any right to usurp.

The Levellers would demand a far greater public accountability by all those who exercise centralised civil, political, scientific, technical, educational and mass media power through the great bureaucracies of the world, and would call for the democratic control of it all.

The Levellers would warn against looking for deliverance to any elite group, whatever its origins, even if it came from the Labour movement, who might claim some special ability to carry through reforms by proxy, free from the discipline of recall or re-election.

The Levellers would argue passionately for free speech and make common cause, worldwide, with those who fight for human rights against tyrants and dictators of all political colours

Also the Levellers called for an elected judiciary and an end to both elitism and elitist terminology with regard to the law. So I do not believe they would have been wholly satisfied with our current legal system and they certainly would have been horrified by the law-making powers of our unelected and unaccountable Brussels commissioners.

With this in mind I feel that the use of the colour Sea-Green as a political/philosophical statement would give provide us with a highly visible and unified identity. Sea-green could easily be adopted by any individual or group who is committed to fighting for the protection and expansion of liberty, democracy and human rights. Now, has anyone got any sea-green cloth?

Further reading

A. C. Grayling ‘Towards the Light: The Story of the Struggles for Liberty and Rights That Made the Modern West‘

A concise history of how people fought and died to secure our liberties.

Dominic Raab ‘The Assault on Liberty: What Went Wrong With Rights‘

How we have lost basic liberties and rights in recent years.

Yesterday I said…

anyone who bothers to look at the real, everyday history of the English working class will find a tradition to be – dare I say it… – proud of.

And lo and behold today The Witanagemot Club have linked to a review (in the Financial Times of all places) of a new book by David Horspool entitled ‘The English Rebel: One Thousand Years of Troublemaking from the Normans to the Nineties.‘

Jackie Wullschlager’s full review can be found here, but I found the following to be of particular significance…

History belongs to the victors – or as Sir John Harington put it in 1618: “Treason doth never prosper, what’s the reason? / For if it prosper none dare call it treason”. Rebels who fail tend not to build the monuments – castles, palaces, civic squares – that are our visible heritage. Yet, says David Horspool in this vivid, lucid chronicle, rebels have shaped England’s character as incontrovertibly and effectively as the monarchs and law-givers they challenged.

Beginning with the Norman conquest and closing with Arthur Scargill, Horspool argues in The English Rebel that England’s role as coloniser – of its own island, then its archipelago, eventually of a third of the world – shrouds the significance of the rebel tradition at home. Anglo-Saxon uprisings led by “woodsmen” who attacked Norman strongholds, then melted into forests and marshes, belong to a lineage running from the Robin Hood myth to today’s eco-warriors. Five centuries before America’s Bill of Rights, English barons forced King John to accept the Magna Carta, sowing the seeds of constitutional reform. Generations ahead of the French Revolution, the English executed Charles I in favour of a radical government.

Most revolts were short-lived, though their inspiration could last much longer. In the 1980s Margaret Thatcher outmanoeuvred the miners but was brought down by protests against a “community charge” – an issue acquiring political resonance when recast as a “Poll Tax”, a byword for injustice during the Peasants’ Revolt 600 years earlier. That earlier revolt arose from successful reactions by the knights of Edward III against demands to supplement the royal coffers; Horspool shows how, repeatedly, when groups higher up the social ladder reaped rewards from limited rebellions, they exposed those beneath them to greater depredations, as well as passing on examples of violent resistance. So revolt became a crucial undercurrent in the slow progress towards parliamentary democracy.

England’s rebels are illuminating, Horspool says, in the context of today’s “search for English identity, for what makes the English different … addressed with increasing urgency as Scottish, Welsh and Irish identity becomes ever more defined… A book about the Irish, Scottish or Indian rebel would tap into a well-recognised tradition”.

I have a deeply held belief that the Liberties of England are an ancient and ongoing project that has yet – if ever – to reach full fruition. As well as ‘revolt’ being ‘a crucial undercurrent in the slow progress towards parliamentary democracy‘ I think it still has an important part to play in the next phase of English politics. Indeed, in an age of uncertainty, would it be too much to hope that the English Rebel still walks among us?

The English Rebel

Review by Jackie Wullschlager

Published: August 10 2009 05:49 | Last updated: August 10 2009 05:49

// 0){if (nl.getElementsByTagName(“p”).length>= paraNum){nl.insertBefore(tb,nl.getElementsByTagName(“p”)[paraNum]);}else {if (nl.getElementsByTagName(“p”).length == 3){nl.insertBefore(tb,nl.getElementsByTagName(“p”)[2]);}else {nl.insertBefore(tb,nl.getElementsByTagName(“p”)[0]);}}}}

// ]]> The English Rebel: One Thousand Years of Troublemaking, from the Normans to the Nineties

The English Rebel: One Thousand Years of Troublemaking, from the Normans to the Nineties

By David Horspool

Viking £25, 432 pages

Despite the leader of the British National Party (BNP), Nick Gri₤₤in, famously calling England ‘a slum’, he claims to love English folk music and has revealed that he intends to launch his own ‘folk’ radio show. But, as with all politicians, he appears to have a hidden agenda.

This weekend the BBC revealed how the BNP used one of Steve Knightly‘s songs, ‘Roots’, to raise money for their extreme right political party without his consent. When Steve discovered that one of his songs was being used on the BNP website he said…

“It’s a betrayal of your invention, you feel violated. We try to make music that’s inclusive. And when organisations like the BNP come along and say ‘this music is ours, this isn’t for black people or Jewish people or whatever’ – that’s a betrayal of what you’ve been working for.”

One of Folk Music’s brightest stars, Jon Boden, has also had found his music being taken out of context by the BNP. Along with many (many…) other projects, Jon performs with Bellowhead – the best live music act in the world!!! – and is currently one of the most influential men in British folk music, but he has found that this cannot protect his work from being misappropriated. Jon recorded several tracks for a folk album that he was told would be sold through gift shops, but he was shocked to find that it went on sale to raise money for the BNP. He says…

“The CD was titled ‘A Place Called England’, but suddenly when you see it on the BNP’s website, it takes on a darker significance that you never imagined.”

The problem is that artists have a very limited say about where and how their recorded music is used. So a new initiative is hoping to put an end to the misappropriation of British folk music. ‘Folk Against Fascism (FAF)‘ (the site should be up and running in September, but you can already join the mailing list or their Facebook group) was officially launched at Sidmouth Folk Festival last week. They hope to encourage musicians to include their logo on their CDs to make it awkward for far-right parties to sell the music or to use it for promoting their causes.

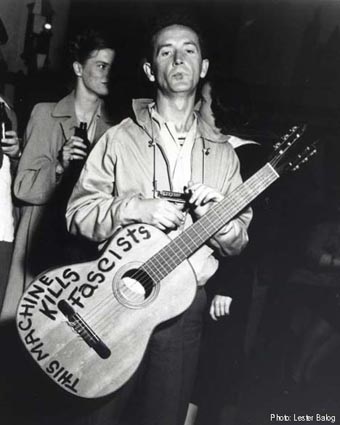

FAF’s logo is, of course, modelled on Woody Guthrie’s famous guitar…

Guthrie knew the power of music and so does FAF’s founder, Joan Crump, who says…

“Music has been a very powerful political tool, usually for the left. What concerns me is that the BNP could do the same thing from a far-right perspective.”

The BNP are said to be looking for a ‘musical soundtrack’ which will help rally people to their cause. I sincerely hope that FAF can ensure that the BNP don’t hijack folk music for these ends, but I fear that simply labelling the BNP and the far-right as ‘fascist’ may not be enough to defend the music I love. As RedStarCommando‘s blog post ‘Give Up Anti-Fascism‘ shows it hasn’t been enough to stop them with regard to elections.

FAF is an important step forward, but if it is to be truly effective it must endeavour to educate people about the real history of folk in general and British folk in particular.

Most folk music is inspired by the working class’ struggle against the oppressive forces of the wealthy and the powerful and is therefore inherently anti-fascist. Writing in The Guardian recently Marek Kohn said…

Whereas folkish nationalism sees folk music as the culture of a people, some of the most influential strands in revived and reworked folk music have seen folk songs as the culture of “the people”, a group defined in opposition to their lords and masters, rather than to counterparts in other lands. The idea of connecting with the people still strikes chords – and folk’s substantial communist heritage still seems to be regarded as perfectly unproblematic.

But like so many on the left he underplays the importance of a shared cultural history. Interestingly enough he also quoted Steve Knightley who urges the English to “rediscover … their musical identity” because “we need roots”, but responds…

Do we really, though? We need depth and we need substance, but we are not plants. At different times different peoples may need the strength that their roots give them, but at this point in history the English scarcely lack sources of support or enrichment. We enjoy affluence and access to knowledge far beyond the imaginations of those unknowns who created the ballads of the British folk canon.

Apart from ignoring the facts that Britain remains one of the most class divided societies on the planet and that high levels of affluence have brought equally high levels of anxiety, depression and suicide thanks largely to the alienating nature of our rootless consumer existence; this statement reflects a widely held feeling on the left that the cultural history of a country should be abandoned for fear that any positive statement could be confused with ardent nationalism.

But anyone who bothers to look at the real, everyday history of the English working class will find a tradition to be – dare I say it… – proud of.

History, as Alex Haley famously said, “is written by the winners” and English history is usually presented as a list of Kings and Queens which begins in 1066 and peaks with the Victorian imperialism of the British Empire. But this is the history of a privileged and the powerful elite. The real history and culture of England is enshrined by tales (both factual and mythical – i.e. folklore) of everyday people who have stood up to excesses and abuses of power in favour of the Liberties of England as enshrined by Magna Carta (which, as Peter Linebaugh demonstrates in his groundbreaking The Magna Carta Manifesto: Liberty & Commons for All, remain of global importance).

England is the home of Robin Hood and ‘Freeborn’ John Lilburne; Ned Ludd and Wat Tyler; Captain Swing and Bartholomew Steer. An overwhelming number of our popular histories, myths and legends contain within them the core English values of liberty, solidarity, collectivism, mutuality, political radicalism, social justice and self-determinism. We would do ourselves an immense disservice if we were to disregard such a rich cultural heritage in the name of ideology or, worse still, political correctness.

Instead folklorists, historians and musicians should endeavour to present a more balanced view of English history, culture and tradition; one that celebrates the English working class and the Liberties of England. As I attempted to show with regard to the issue of ‘blacking‘ in Border Morris, a deeper understanding of our traditions is the best weapon against fear, hatred and ignorance.

Music may indeed be a powerful tool; but so is knowledge.

Further reading

George Orwell ‘Essays‘

The essays of George Orwell may have been written over 60 years ago, but they remain relevant to the ‘English experience’ and manage to balance a love of England with a hatred of ardent nationalism. Of particular interest to this article would be The Lion & The Unicorn, My Country Left or Right and Notes On Nationalism.

E. P. Thompson ‘The Making of the English Working Class‘

The book that revolutionised our understanding of English social history.

Paul Kingsnorth ‘Real England‘

Paul Kingsnorth searches for an English cultural and political identity which is based on ‘being’ rather than ‘belonging’, or, as Paul says, “a new type of patriotism, benign and positive, based on place not race, geography not biology.”

The blog for Paul’s book can be found here

The law locks up the man or woman

Who steals the goose from off the common

But lets the greater villain loose

Who steals the common from the goose- AnonymousIn every cry of every Man,

In every Infants cry of fear,

In every voice: in every ban,

The mind-forg’d manacles I hear.- William Blake

Earlier this year the Motley Morris troupe from Dartford, Kent were booked to dance at a primary school, but when the school found out that their routine involved ‘blacking’ – the use of burnt cork to paint the dancers faces – they were asked not to attend due to fears they could cause offence.

A spokesman for Motley Morris, Simon Fordis was quoted in The Independent as saying…

“Our style of morris dancing originates from the Welsh/Shropshire borders. Our blackened faces are a form of disguise. Traditionally they used burnt cork, which came out black, but if it had come out red then we would have had red faces, that’s all it is. It’s part of our English culture which goes back hundreds of years, it’s an age-old tradition. [sic]They said it was supposed to be a cultural evening but they hadn’t even bothered to find out why it is we have blackened faces. They’re obviously afraid of upsetting someone.”

The headteacher of the school stated…

“We found ourselves in a difficult position of weighing up any potential offence versus not wishing to compromise the morris dancers’ tradition. It’s a ‘damned if we do, damned if we don’t’ scenario and quite understandably it will be a talking point as to the rights and wrongs of our decision. I apologise to the morris troupe for any inconvenience caused and ask for people’s understanding at what was a difficult but well intended decision.”

This is indeed a ‘damned if we do, damned if we don’t’ issue, but it is one that has been confounded by an ignorance of working-class history and by our currently shallow, point-scoring, right-vs-left, political culture. Obviously far-right bloggers made a big deal of this event with the usual “What about the indigenous (meaning ‘white’) English and their traditions” line (the far right like to talk about ‘history’ and ‘tradition’, but show little knowledge of either), whereas the right wing in general replied with the incredibly hackneyed “Political Correctness gone mad”. But the ‘right-on’ left were equally as predictable with their “morris is a Victorian invention” and “imperialist traditions” type comments.

Which is a shame because if they had bothered to look deeper they would have found that blacking was once an aspect of an everyday, grassroots movement which fought for social, economic and racial equality.

You may be wondering why morris dancers need a ‘disguise’; are they really that embarassed by their hobby? Obviously there’s more to this tradition than some fancy footwork.

A chapter of Peter Linebaugh’s incredibly important book, “The Magna Carta Manifesto: Liberty & Commons For All” (UC Press, 2008), entitled ‘Charters of Liberty in Black Face and White Face: Race Slavery & The Commons’ deals specifically with the themes of blacking and race. I recommend that you buy this book or ask your local library to stock it; luckily if you are unable – or unwilling – to get your hands on a copy, the cool guys at Mute magazine have an online version of the chapter in question; this chapter on it’s own acts as a great introduction to the ideas presented in Linebaugh’s book.

Linebaugh reveals that blacking was used as a disguise by people who were fighting for their traditional Liberties as guaranteed under Magna Carta. He describes the fateful events which led to the notorious Waltham Black Act of 1722 and shows that it wasn’t just ‘poaching’ which led to the passing of this law. After coming across the anonymously published The History of the Blacks of Waltham in Hampshire (1723) Linebaugh became convinced that he needed to…

put forward the fact that the poachers defended commoning, not just by disguising themselves but by disguising themselves as Negroes, and they did so at Farnham, near the heart of what became the quintessence of England as Jane Austen so gently wrote about it, or Gilbert White, the ornithologist, so carefully observed it, or William Cobbett, the radical journalist, so persistently fulminated about it.

He goes on to describe the events at Farnham, a town north of Portsmouth and just 60 miles Southeast of Motley Morris’s hometown of Dartford and shows how this the stage for a legal definition of ‘race’…

Round about Farnham timber was wanted for the construction of men-of-war and East Indiamen which stopped in Portsmouth for repairs, or were built there from scratch for the purpose of the globalisation of commodity trade characteristic of the time. Here’s how a flashpoint in the episodes of the Waltham Blacks began: ‘Mr. Wingfield who has a fine Parcel of growing Timber on his Estate near Farnham fell’d Part of it: The poor People were admitted (as is customary) to pick up the small Wood; but some abusing the Liberty given, carry’d off what was not allow’d, which that Gentleman resented; and, as an Example to others, made several pay for it. Upon which, the Blacks summon’d the Myrmidons, stripp’d the Bark off several of the standing Trees, and notch’d the Bodies of others, thereby to prevent their Growth; and left a Note on one of the maim’d Trees, to inform the Gentleman, that this was their first Visit; and that if he did not return the Money receiv’d for Damage, he must expect a second from … the Blacks.’ This is not exactly tree-hugging or Indian chipko, though it did have warrant among local antiquarians in the nineteenth century who searched for a charter of such commoning. The leader of the Blacks and ‘15 of his Sooty Tribe appear’d, some in Coats made of Deer-Skins, others with Fur Caps, &c. all well armed and mounted: There were likewise at least 300 People assembled to see the Black Chief and his Sham Negroes….’

Charles Withers, Surveyor-General of Woods, observed in 1729 ‘that the country people everywhere think they have a sort of right to the wood & timber in the forests, and whether the notion may have been delivered down to them by tradition, from the times these forests were declared to be such by the Crown, when there were great struggles and contests about them, he is not able to determine.’ The Waltham Blacks, they said, ‘had no other design but to do justice, and to see that the Rich did not insult or oppress the poor.’ They were assured that the chase was ‘originally design’d to feed Cattle, and not to fatten deer for the clergy, &c.’ The central common right was pasture, ‘common of herbage’ as the Forest Charter says. Keeping a cow was possible on two acres, and less in a forest or fen. Half the villagers of England were entitled to common grazing. As late as the 18th century ‘all or most householders in forest, fen, and some heathland parishes enjoyed the right to pasture cows or sheep.’ So, the Waltham Blacks were class conscious. There was also an awareness at the time that the keeping of a cow, essential to the material constitution of the country, was backed up by charter.

Timothy Nourse denounced commoners at the beginning of the century. They were ‘rough and savage in their Dispositions.’ They held ‘leveling Principles.’ They were ‘insolent and tumultuous’ and ‘refractory to Government.’ In September 1723 Richard Norton, the Warden of the Forest of Bere, wished to ‘put an end to these arabs and banditti.’ The commoner belonged to a ‘sordid race.’

The commoner was compared to the Indian, to the savage, to the buccaneer, and to the Arab.(emphasis added)

The ‘Blacks’ defended the customs of the commoners; the commoners were both criminalised and racialised in the discourse of the enclosers, the privatisers, and the big wigs. There was even the suggestion that attacking them was a sort of crusade. The Waltham Black Act of 1722 thus became, among other things, a means of drawing a colour line and criminalising common right.

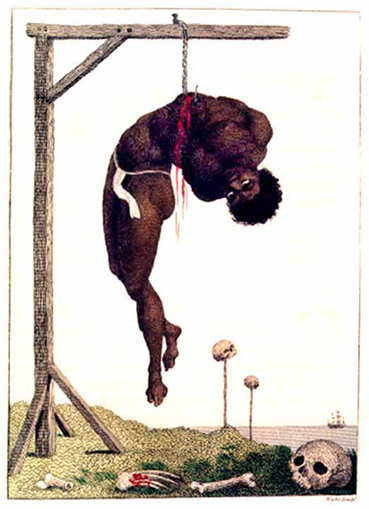

This drawing of the ‘colour line’ – and indeed the Waltham Black Act – was to prove essential to the development of one of the largest and most hideous trades in history – the slave trade.

William Blake

Naturally the slave trade went against ‘Christian values’ and the belief that ‘all men are equal before God’, but it was big business and – as well we know from that day to this – money-men will stop at nothing to make a profit. As ever divide and conquer was the preferred strategy…

A buffer stratum was to be created by offering material advantages to white proletarians to the lasting detriment of black proletarians. When and how did the ‘wages of whiteness’ originate? The first date DuBois gives in the protracted process is 1723 when laws were passed in Virginia making Africans and Anglo-Africans slaves forever. The bonded people objected in 1723 to the Bishop of London and the King ‘and the rest of the Rullers.’ ‘Releese us out of this Cruell Bondegg’ they cried. In the same year Richard West, the Attorney General, objected to the same law, ‘I cannot see why one freeman should be used worse than another, merely upon account of his complexion….’ But the Governor of Virginia understood the necessity of ‘a perpetual Brand’ – skin colour, or the phenotype, which marked the person as surely as the burnt flesh caused by the golden brands used by the South Sea Company. In this way, Ted Allen tells us, a ‘monstrous social mutation’ occurred, namely, that stratum within the American class structure which derives its hopes, security, and welfare from white skin privilege. It has been essential to the constitution of American class relations ever since.

Slavery was abolished in England in 1807, The Black Act was abolished in 1823 and the Slavery Abolition Act was introduced in 1833, but the colour line that the Black Act and the Slave Trade helped to create remains politically and socially divisive to this day.

Ignorance lies at the heart of bigotry; unfortunately the politically correct left seem to be willfully ignorant of English working-class traditions, even though these traditions can reveal a cultural history that could bring modern English citizens – of all races – closer together.

“We found ourselves in a difficult position of weighing up any potential offence versus not wishing to compromise the morris dancers’ tradition.

“It’s a ‘damned if we do, damned if we don’t’ scenario and quite understandably it will be a talking point as to the rights and wrongs of our decision.

“I apologise to the morris troupe for any inconvenience caused and ask for people’s understanding at what was a difficult but well intended decision.”